The OECD real estate reporting framework represents a structural expansion of global tax transparency, bringing immovable property into automatic cross-border information exchange.

Through the Multilateral Competent Authority Agreement on the Exchange of Readily Available Information on Immovable Property (IPI MCAA), tax authorities can now systematically share data on foreign-owned real estate.

This reduces opacity in one of the last major asset classes outside international reporting standards.

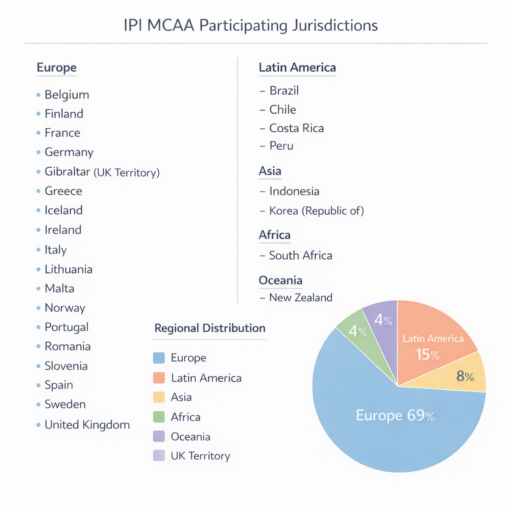

Early pledges come from a mix of European, Latin American, African, Asian, and Oceania jurisdictions.

Key Takeaways:

- Real estate is now part of OECD tax transparency, alongside financial and digital assets.

- The IPI MCAA enables automatic exchange of property ownership and income data.

- Offshore property structures remain legal, but opacity is no longer sustainable.

- Property planning now hinges on alignment across ownership, reporting, residency, and substance.

My contact details are hello@adamfayed.com and WhatsApp +44-7393-450-837 if you have any questions.

The information in this article is not tax advice and may have changed since the time of writing. I can connect you with expert tax support for your specific situation.

Why the OECD is Focusing on Real Estate Now

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) is focusing on real estate because it has historically fallen outside the scope of international tax transparency standards.

This has remained the case despite real estate representing a significant store of international wealth.

For more than a decade, transparency efforts have concentrated on financial assets—bank accounts, securities, and investment funds under FATCA and CRS, with crypto assets now captured through CARF.

Real estate, by contrast, remained fragmented across domestic land registries, municipal tax offices, and corporate vehicles. Hence, capital mobility increased, but property visibility did not.

From the perspective of the OECD, this gap became untenable for three reasons:

- First, real estate is frequently used as a long-term store of wealth by non-residents, particularly in stable jurisdictions.

- Second, property ownership is often layered through companies, trusts, or nominee arrangements that complicate enforcement.

- Third, governments face mounting fiscal pressure, making foreign-owned domestic property an obvious enforcement target.

The move toward real estate transparency is practical. Property data already exists—what was missing was cross-border connectivity.

What is the OECD Real Estate Reporting Framework?

The OECD real estate tax transparency reporting framework is a standardized approach for collecting and automatically exchanging information on immovable property between tax authorities.

Rather than imposing an entirely new reporting regime on taxpayers at the outset, the framework is built around readily available information.

That means data that governments already hold or can access without fundamental system redesign.

This typically includes:

- Legal ownership records from land or title registries

- Identifiers linking property to individuals or entities

- Valuation or transfer price data

- Rental income or usage classification where available

The framework’s innovation lies in data integration. Property information that once remained domestically contained is now formatted, standardized, and exchanged across borders.

What is the Multilateral Competent Authority Agreement (IPI MCAA)?

The IPI MCAA is the legal mechanism that enables countries to exchange real estate information automatically and multilaterally.

Formally known as the Multilateral Competent Authority Agreement on the Exchange of Readily Available Information on Immovable Property, it functions in a similar manner to CRS-related agreements.

However, IPI MCAA applies to property instead of financial accounts.

From a governance standpoint, the agreement offers several advantages:

- A single multilateral framework instead of multiple bilateral treaties

- Standardized data fields and exchange timelines

- Flexibility in implementation depth based on domestic systems

- Legal clarity for routine, non-request-based exchanges

Crucially, the agreement does not require every participating country to exchange with every other country immediately.

Pairings are activated progressively, allowing the network to expand organically.

What is the Automatic Exchange of Readily Available Information on Immovable Property?

It is the routine, systematic sharing of property-related data between tax authorities without the need for a specific enquiry or investigation.

Once exchanges are activated, participating jurisdictions may receive information such as:

- Property owned domestically by non-residents

- Real estate held through companies, partnerships, or trusts

- Rental income attributed to foreign owners

- Transfer or disposal events indicating potential capital gains

Unlike traditional information exchange on request, this process is proactive rather than reactive. Authorities do not need suspicion to receive data; visibility is built into the system.

This represents a shift in enforcement, as foreign property ownership is treated as inherently reportable, not exceptional.

How OECD Real Estate Tax Transparency Fits Broader Standards

The OECD reporting rules for real estate complement existing international tax transparency standards rather than replace them.

Taken together, the OECD’s initiatives now cover:

- Financial accounts (CRS-style reporting)

- Corporate and beneficial ownership registers

- Digital platforms and seller income

- Crypto-asset reporting frameworks

- Immovable property via the IPI MCAA

The direction of travel is consistent. Each framework targets an asset class that was previously fragmented, under-reported, or jurisdictionally siloed.

From a policy perspective, the message targets asset class neutrality. Whether wealth sits in cash, securities, tokens, or land, the expectation is that it will be visible somewhere in the system.

What countries are part of the IPI MCAA?

The IPI MCAA countries list continues to expand but primarily includes those already aligned with OECD transparency standards, such as France, Singapore, Canada, and the Netherlands.

Below are the 26 jurisdictions that publicly committed to implement the IPI MCAA, aiming to join by 2029/2030, based on the OECD’s joint statement and subsequent reporting:

| Belgium | Indonesia |

| Brazil | Ireland |

| Chile | Italy |

| Costa Rica | Korea (Republic of) |

| Finland | Lithuania |

| France | Malta |

| Germany | New Zealand |

| Greece | Norway |

| Iceland | Peru |

| Portugal | Romania |

| Slovenia | South Africa |

| Spain | Sweden |

| United Kingdom | Gibraltar |

Countries most likely to participate share common characteristics:

- Centralized or digitized land registries

- Existing experience with automatic exchange under CRS

- Political commitment to international tax cooperation

- Fiscal incentives to monitor foreign ownership

That said, participation is not uniform. Differences exist in:

- Data granularity (legal vs beneficial ownership)

- Frequency of exchange

- Types of property covered

- Treatment of indirect ownership

These variations matter. In the short to medium term, they create asymmetric transparency, where some jurisdictions exchange more data than others.

For planners, understanding these nuances is essential—but relying on them indefinitely is not a strategy.

Non-Reporting Jurisdictions: What Happens If You Don’t Report?

While the IPI MCAA is designed to expand automatic information exchange, participation is currently not universal.

Some jurisdictions have not yet signed on, and others may be outside the scope of existing frameworks such as CRS or CARF.

So, can you not report? Only temporarily.

If a property is located in an IPI MCAA country, reporting is mandatory for local custodians, registries, and financial institutions.

Non-compliance can trigger penalties, audits, or restrictions on cross-border transactions.

Properties held in countries not yet participating are not automatically exchanged under the IPI MCAA.

While this may temporarily reduce transparency, it does not exempt investors from tax obligations in their home countries.

Domestic tax authorities may still require disclosure of foreign property holdings.

How OECD Tax Reporting Changes Offshore Real Estate Structuring

OECD real estate tax transparency does not prohibit offshore property ownership, but it removes opacity as a structural advantage.

Historically, many international property arrangements relied on the assumption that foreign tax authorities would struggle to detect or contextualize overseas real estate holdings.

Such assumption is now weakening.

As exchanges mature, authorities can more easily:

- Cross-check property ownership against declared residency

- Identify mismatches between income reporting and asset holdings

- Question legacy SPVs with minimal substance

- Detect undeclared rental income or disposals

This does not mean all offshore property structures are flawed. It does mean that structures must now be defensible, not merely discreet.

The Shift From Concealment to Coherence

At a strategic level, the OECD’s real estate initiative signals a broader reframing of international planning.

The old paradigm rewarded complexity. Multiple layers, jurisdictions, and intermediaries increased friction for enforcement.

The new paradigm rewards coherence where ownership, control, use, and tax reporting tell a consistent story across borders.

This means:

- Substance matters more than form

- Reporting consistency matters more than secrecy

- Long-term sustainability matters more than short-term arbitrage

For globally mobile individuals, this is less a restriction than a recalibration. Planning remains possible, but it operates within clearer informational boundaries.

Why Offshore Real Estate Stayed Hidden Until Now

Real estate was never invisible because governments lacked data but because data stopped at borders.

Land registries, cadastral systems, and municipal tax databases were designed for domestic administration, not international exchange. The IPI MCAA bridges that design gap.

Once property data is standardized and exchanged, it becomes analytically powerful, especially when combined with CRS data, migration records, and corporate registries.

This is why the OECD’s move matters as it converts static domestic records into dynamic cross-border intelligence.

Practical Implications for Expats and International Investors

For expats, second-home owners, and internationally diversified families, the implications are practical rather than theoretical.

Key questions now include:

- Does the ownership structure still align with my tax residency?

- Is rental income reported consistently across jurisdictions?

- Are holding entities defensible under substance and control tests?

- Would exchanged data tell a coherent story if reviewed holistically?

Answering these questions early is far less costly than addressing them after an enquiry.

Bottom Line

The OECD real estate reporting framework and IPI MCAA bring immovable property fully into international tax transparency standards, ending its status as a structurally obscure asset class.

For investors and advisors, the real risk is not transparency itself, but misalignment—between structures built for yesterday’s environment and today’s enforcement reality.

In a world of automatic exchange, good planning is no longer about avoiding visibility but ensuring that visibility makes sense.

FAQs

Are multilateral agreements legally binding?

Yes. Multilateral agreements are legally binding for the countries that sign and ratify them.

Once ratified, participating states are obligated to comply with the terms under international law, and failure to do so may lead to diplomatic consequences or sanctions.

What are the advantages of multilateral agreements?

Multilateral agreements offer several benefits:

• Standardization: Create uniform rules across multiple countries.

• Efficiency: Reduce the need for numerous bilateral agreements.

• Predictability: Provide clarity for cross-border activities like taxation, trade, or investment.

• Cooperation: Facilitate collective action on global issues, such as tax transparency or environmental standards.

What is classified as immovable property?

Immovable property refers to assets that are permanently fixed to a location, making them immobile.

Examples include land, buildings, and structures permanently attached to land, as in houses, apartments, plots, and certain legal rights tied to real estate.

Who is CRS applicable to?

The Common Reporting Standard (CRS) applies to financial institutions and their account holders in participating jurisdictions. It primarily targets:

• Individuals and entities with tax residence in CRS-participating countries

• Foreign account holders whose financial information must be reported to their home tax authority

Who needs to fill in FATCA?

US persons with foreign accounts and foreign financial institutions holding accounts for US persons. Reporting is done via Form 8938 or through FATCA-compliant financial institutions.

Which countries do not report to FATCA?

Very few jurisdictions do not report to FATCA, usually because they haven’t signed an Intergovernmental Agreement with the US, such as Afghanistan, Jordan, and Egypt.

Even in these cases, US taxpayers are still legally required to disclose their foreign accounts to the IRS.

Pained by financial indecision?

Adam is an internationally recognised author on financial matters with over 830million answer views on Quora, a widely sold book on Amazon, and a contributor on Forbes.