What is the benefit of getting an investment advisor or consultant?

We live in a world where people can invest online into many different assets.

Therefore, what are the main benefits associated with good financial or investment consultants/advisor?

Below is a list.

Table of Contents

Access to different kinds of assets

It might be possible to gain access to ETFs, funds and many different assets on your own.

However, an investment advisor can give you access to opportunities that aren’t usually available to the average, or even wealthy, investor.

Some investment opportunities are institutional in nature, such as some forms of alternative assets linked to property and certain corporate bonds.

The 60%-40% rule is “almost dead”.

The 60%-40% portfolio was simple. 60% should go into stocks and 40% in bonds. Those assets are easy to get hold of yourself.

The problem is, government bonds and cash have been paying less than inflation for over a decade.

Until that changes, the 60%-40% portfolio doesn’t make sense.

Therefore, seeking alternatives becomes important, especially with bank deposits looking increasingly unsafe.

Access to a network

Most advisers or consultants are specialized. For example, we specialise in investments for high-net-worth individuals and expats.

We naturally have access to specialists in areas such as law (wills, probate etc), insurance, mortgages and many other areas.

Sometimes we can give existing clients a discount on those kinds of services and trusted recommendations.

Emotions

Be honest. How good are you at going to the gym?

If you are like me, my self-motivation comes and goes. In comparison, when I had a trainer, I always went to the gym, because I had appointments in my diary.

Yes, rationally speaking, it would be more efficient if the trainer gave me pointers over a few sessions, and then I continued alone.

Human nature being what it is, I made more progress keeping to a plan and having somebody to hold me to account, who was being paid for doing so.

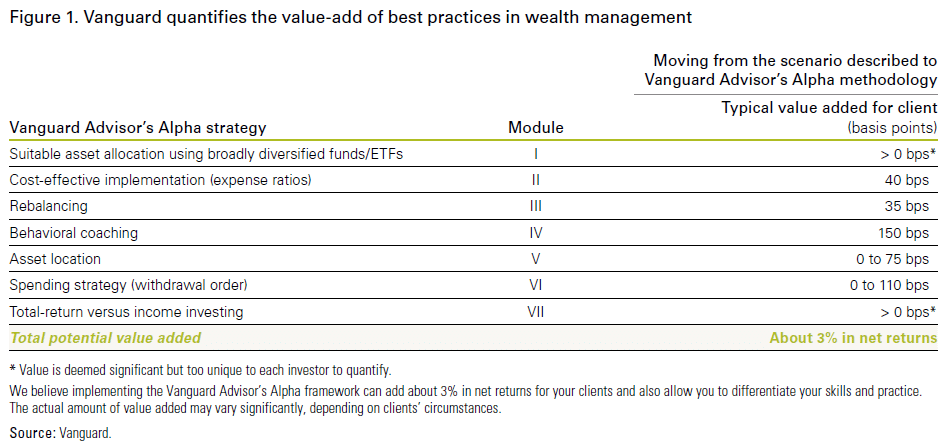

Even if we exclude the arguments about alternative assets, firms like the Vanguard Group have found that advised clients get better (on average) returns than do-it-yourself (DIY) ones.

They even tried to calculate the benefits associated with advisors, as per the table below:

Yes, that does mean that even invested in the same funds and paying higher fees, advised clients “beat” DIY clients.

What could explain this? It is simple. Emotions. Nobody cares about your own money as much as yourself, but that is the problem.

A good advisor will take emotion out of the process and invest you properly.

We have seen the benefits of this in recent years.

When stock prices crashed in February 2020, few DIY investors want to put money to work. Come the recovery, “everybody” seemed to want to invest.

Likewise, fewer people invested after the Russia-Ukraine war, and even sold out.

Many investors who “did their own research” also got stung by Cathy Wood’s fund, as detailed on the video I did below:

These emotions ensure that many people buy high and sell low.

Potentially reducing hassles

You might be dealing with an investment company, or bank, which is difficult to deal with, due to pointless processes.

Advisors, consultants and firms that keep things simple could save you hassles.

Saved time

Time is money. You need to adjust return on investment (ROI) for time spent.

If people do this, they will find they are often making little money or even losing out.

For example, making 10% per year net of expenses in property won’t make sense if you are spending too much time on maintenance.

Pained by financial indecision? Want to invest with Adam?

Adam is an internationally recognised author on financial matters, with over 760.2 million answer views on Quora.com, a widely sold book on Amazon, and a contributor on Forbes.