In today’s podcast I discuss stories related to digital sales tax on online businesses

Will this be the next frontier in global taxes post-covid, alongside expat and wealth taxes, which I recently discussed relating to Argentina and the UK?

That certainly seems to be the case, with the EU, Cambodia and countless other countries pondering bringing in some new taxes on tech firms.

I will also discuss some of the latest economic numbers coming out of countries like the UK and New Zealand.

They seem to be diverging but is there a common theme around the world?

Should people rush to put money in the New Zealand stock market?

For your convenience, and to give credit to the original writers, I have included links to the articles I referred to and copied them below.

EU states agree to share digital platform information to aid tax collection – MNE Tax

The EU Council has reached a technical agreement on the exchange of information related to digital platforms, such as Amazon, Airbnb. The exchange will help EU states assess and collect the appropriate amount of income tax and VAT due by EU and non-EU sellers that use the platforms.

Indeed, the EU is planning a new amendment to the well-known Directive on Administrative Cooperation – 2011/16/EU. Even though its application is already broad, the exchange of information mechanism will be extended to the huge database related to digital platforms.

The adoption of a DAC 7 directive will represent a step forward in the fight against tax evasion and tax avoidance. Most of the taxable income of the sellers on digital platforms flow cross-border. Only by improving cooperation will tax authorities be able to assess income taxes and VAT due in a proper manner.

According to the agreement, reached on 25 November, the eligible digital platforms, even those sited in a non-EU country, must collect all information related to sellers, sorted by Member State.

The already-operational EU automatic exchange of information mechanism will be exploited and enhanced.

Moreover, this is the occasion for the EU to improve some aspects of this important tool.

Indeed, among other adds, DAC7 will introduce in the core of the directive a provision defining the foreseeable relevance criteria and clarification to ease group requests. Joint audits will be strengthened.

Indeed, among other adds, DAC7 will introduce in the core of the directive a provision defining the foreseeable relevance criteria and clarification to ease group requests. Joint audits will be strengthened.

The agreement is not without criticism. It is worth mentioning once more the absence of any reference to taxpayers’ rights except in the case of a data breach.

The Council will adopt the DAC7 after the receipt of the opinions of the European Parliament and the European Economic and Social Committee, presumably within the next weeks.

Facebook, Google and Microsoft ‘avoiding $3bn in tax in poorer nations’ – BBC

Google, Facebook and Microsoft should be paying more corporation tax in developing nations, says ActionAid.

The aid charity estimates that poorer countries are missing out on up to $2.8bn (£2.2bn) in tax revenue that could be used to tackle the pandemic.

ActionAid is calling for big companies to pay a global minimum rate of tax.

Facebook and Microsoft declined to comment while Google did not immediately respond to a request for comment.

Multinational corporations are currently not required by law to publicly disclose how much tax they pay in some developing countries.

According to ActionAid, “billions” might be at stake that could be used to transform underfunded health and education systems in some of the world’s poorest countries, especially since multiple tech giants have reported soaring revenues during the pandemic.

The aid charity wants to see a new global tax system created, preferably by the United Nations, whereby large corporations are required to pay a global minimum rate of corporate tax reflective of their “real economic presence”.

ActionAid estimates that $2.8bn could pay for 729,010 nurses, 770,649 midwives or 879,899 primary school teachers annually in 20 countries across Africa, Asia and South America.

The aid charity said its research showed that the developing nations with the highest “tax gaps” from Google, Facebook and Microsoft are India, Indonesia, Brazil, Nigeria and Bangladesh.

“Women and young people are paying the price for an outdated system that has allowed big tech companies, including giants like Facebook, Alphabet and Microsoft, to rack up huge profits during the pandemic, while contributing little or nothing towards public services in countries in the global south,” said David Archer, global taxation spokesperson for ActionAid International.

“The $2.8bn tax gap is just the tip of the iceberg – this research covers only three tech giants. But alone, the money that Facebook, Alphabet (Google’s owner) and Microsoft would be paying under fairer tax rules could transform public services for millions of people”.

Tax avoidance concerns

There have long been concerns that the biggest corporations do not pay enough tax in developed nations, and re-route profits through low-tax jurisdictions.

Facebook, Google, Apple and Amazon have all settled disputes with French tax authorities over their operations in the country over the last decade. And the UK in April launched a new digital sales tax aimed at forcing tech giants to pay more on the income they generate inside the country.

In February, Facebook boss Mark Zuckerberg said he recognised the public’s frustration over the amount of tax paid by firms like his.

He added that Facebook accepted the fact it might have to pay more in Europe “under a new framework” in future, and backed plans by think tank the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) to find a global solution.

It is time for those who have the most to pay the most – Phnom Penh post

The Covid-19 pandemic that has been ravaging our planet for almost a year now has not only killed at least 1.33 million people, caused an explosion of unemployment and deprived hundreds of millions of children around the world of schooling, it has probably also provoked deep disruptions in the world’s economy, the long-term impact of which promises to be far-reaching.

This is true geographically – by the end of next year, according to forecasts by the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), the US economy will be the same size as it was in 2019 but China’s will be 10 per cent larger.

It is also true between sectors: while hospitality, the travel industry or the entertainment world have experienced a collapse of their activities, some companies have found business booming in the new normal. This is especially the case for the tech giants who have seen huge gains as the world has gone almost entirely online for working, shopping, schooling and socialising. Take Amazon – it reported that its net sales increased by an impressive 40 per cent in the second quarter of its fiscal year compared to the same time last year, totalling $88.9 billion.

Ironically, these multinational digital companies are also the champions of tax avoidance. The GAFA, as they are called – Google, Apple, Facebook and Amazon – are not the only ones who do not pay taxes according to their activities, but, because they are dematerialised, they are able to exploit the loopholes in the international tax system more easily. By manipulating transactions between their subsidiaries, they are reporting record profits in tax havens and very low ones – when not losses – in countries with higher corporate taxes, even though they are actually operating extensively in the latter.

Every year, the world is losing over $427 billion in fiscal resources to international corporate tax abuse, as just revealed by The State of Tax Justice 2020, a report launched jointly by Tax Justice Network, Public Services International and the Global Alliance for Tax Justice. It means that countries around the world are on average losing 9.2 per cent of their health budgets to tax havens every year. Cambodia loses the equivalent of 7.89 per cent of what it spends for health, an amount that would allow paying the yearly salaries of nearly 11,000 nurses.

Of the $427 billion, multinational corporations are to blame for nearly $245 billion, thanks to the practice – mostly legal – of “profit-shifting” described above. Wealthy individuals have absconded with the astonishing remaining $182 billion, through the hiding of undeclared assets and incomes in tax havens, beyond the reach of the law.

Already scandalous, this situation has become more unbearable than ever while the global economy is plunging into the worst recession since the Great Depression. In its latest report on the East Asia and Pacific region, the World Bank predicted an annual contraction of activity between 3.5 and 4.8 per cent, with the emergence of a class of “new Covid poor” for the first time in 20 years. Even with the inclusion of China, which has seen a better than expected recovery from the pandemic, the organisation expects the region to grow between 0.3 and 0.9 per cent this year, the lowest rate since the 1960s.

As everywhere in the world, building back will have a cost. It means more money for public services, which have been hard hit by this crisis, especially the health and education sectors. But it will also require countries to spend more on boosting employment and helping small businesses, while investing in preventing future pandemics and fighting climate change – a perspective that sows panic in many governments, which speak of empty coffers and are instead tempted by austerity programmes.

It is time for those who have the most to pay the most. The OECD has been promising for years to put an end to the aberrations that allow the richest and multinationals to escape their tax obligations. But a misplaced sense that national interest is served by protecting multinationals has prevailed over global public needs, and the publication, last month, of the organisation’s complex and disappointing proposals showed that no major changes are expected in the coming months.

In this context, governments should move regionally or unilaterally to introduce interim measures to raise immediate tax revenues, as suggested by the Independent Commission for the Reform of International Corporate Taxation (ICRICT), of which I am a member. They should, for example, apply a higher corporate tax rate to large corporations in oligopolised sectors with excess rates of return.

And since multinationals have owners – even if they are often in hiding – there is also an urgent need to rethink the taxation of individuals in a more progressive way. Indeed, world’s billionaires did very well during the pandemic, increasing their wealth by more than a quarter (27.5 per cent) from April to July, as unveiled recently in a report by Swiss bank UBS. It also means establishing comprehensive public registers of the beneficial owners of companies, trusts and foundations to stop tax evasion from flourishing.

From multinational corporations to the wealthiest individuals, governments now have the technical means to track down tax evaders. It is time for them to demonstrate their political will. The costs of the pandemic are already being borne disproportionately by the poorest and most vulnerable. The economic burden of rescue packages should not fall on them either.

UK GDP growth slows to six-month low as COVID hits hospitality – Reuters

LONDON (Reuters) – Britain’s economic recovery almost ground to a halt in October as a surge in coronavirus cases hammered the hospitality sector, adding to the chances that the economy will shrink over the final three months of 2020.

Thursday’s official data showed the economy lost momentum as public authorities in much of the United Kingdom barred people from socialising in pubs and restaurants, ahead of a broader four-week partial lockdown across England in November.

Gross domestic product rose 0.4% in October after expanding 1.1% in September, the Office for National Statistics said, the weakest growth since output collapsed in April during the first lockdown.

A limited rollout of a COVID vaccine began this week in Britain, offering hope for a rebound in consumer spending in 2021. But many businesses will face new headwinds from trade restrictions with the European Union that come into force on Jan. 1 when post-Brexit transition arrangements end.

Prime Minister Boris Johnson and the EU’s chief executive, Ursula von der Leyen, have given themselves until Sunday to seal a new trade pact that would limit some of the damage, after failing to overcome persistent rifts at a meeting on Wednesday.

“The economy continued to grow in October, but at a snail’s pace. And with the COVID-19 restrictions likely to remain in place for some time, the economy is in for a difficult few months yet,” Ruth Gregory, economist at Capital Economics said.

Britain has Europe’s highest death toll from COVID-19, with more than 62,000 fatalities, and also suffered the biggest economic hit of any major economy after GDP shrank by an unprecedented 19.8% in the second quarter of this year.

Output in October was 7.9% lower than it was in February, before the pandemic struck Britain’s economy, and 8.2% weaker than in October 2019, the ONS said.

Government forecasters do not expect the economy to regain its pre-COVID size until the end of 2022 and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development predicted Britain’s recovery would be weaker than anywhere bar Argentina.

Although the economy picked up rapidly after the initial shock of the lockdown, it lost momentum as COVID cases started to rise again in September and accelerated in October.

Government restrictions that largely barred Britons from socialising with people they did not live with led to a 14.4% fall in output across the accommodation and restaurant sector.

Most economists think GDP fell outright in November, when the British government imposed a four-week partial lockdown in England, closing non-essential shops and hospitality venues, and similar measures were imposed elsewhere in the United Kingdom.

The decline is expected to be more limited than in the first lockdown, when restrictions were tighter and businesses had less time to adapt.

Economists at Morgan Stanley forecast a 3% fall in GDP for the fourth quarter, and said they expected the Bank of England to cut rates to zero from their current 0.1% – possibly as soon as next week, if Brexit trade talks collapsed.

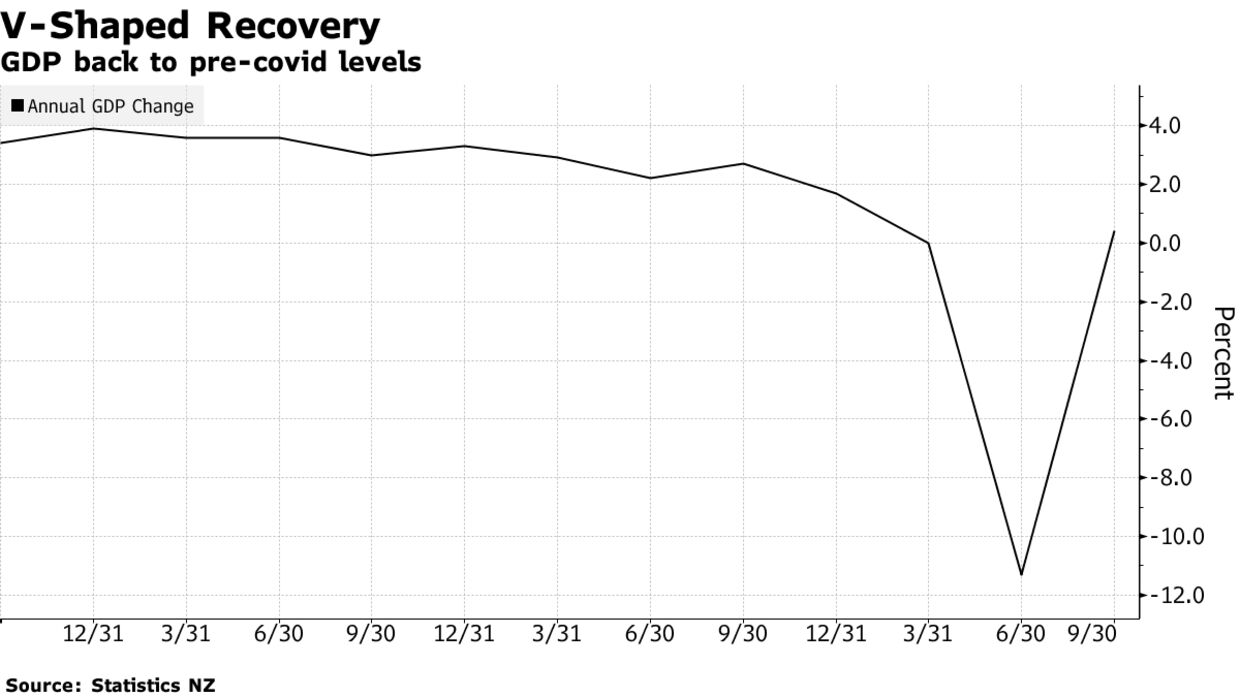

New Zealand Economy Surges Out of Recession In V-Shaped Recovery – Bloomberg.

New Zealand’s economy bounced back strongly from recession in the third quarter, achieving a so-called V-shaped recovery as massive fiscal and monetary stimulus fueled consumer spending.

Gross domestic product surged 14% from the second quarter, when it contracted a revised 11%, Statistics New Zealand said Thursday in Wellington. Economists forecast a 12.9% gain. From a year earlier, the economy grew 0.4%, confounding the consensus forecast for a 1.8% decline.

New Zealanders have gone on a spending spree since the nation eliminated community transmission of Covid-19 in May and then successfully contained sporadic outbreaks. However, the border remains closed to foreigners, crippling the tourism industry, and many businesses have put investment and hiring plans on hold, which is projected to push the jobless rate higher in 2021.

The V-shaped economic rebound is “vindication of the Covid-19 ‘elimination’ strategy New Zealand has pursued, as it has underpinned a strong economic recovery from what has been an unprecedented shock,” said Paul Bloxham, chief Australia and New Zealand economist at HSBC in Sydney. Still, “closed international borders to people movement are weighing on tourism and other services exports, and are set to continue to do so for some time.”

The New Zealand dollar rose after the GDP report and bought 71.29 U.S. cents at 3:52 p.m. in Wellington. The currency has gained 5.5% the past three months, and was appreciating ahead of the release after Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern announced plans to offer Covid-19 vaccines to the entire population in the second half of 2021.

The economy’s quick rebound to pre-Covid levels was a rare feat, said Stephen Toplis, head of research at Bank of New Zealand in Wellington.

“We can only identify three other countries that have achieved the ‘full recovery’: Taiwan, China and Ireland,” he said. “New Zealand is definitely in a very small minority.”

The government’s determination to eliminate the virus saw it impose one of the strictest lockdowns in the world but allowed a quicker resumption of economic activity once it was stamped out. New Zealand has recorded 1,744 confirmed cases of Covid-19 and just 25 deaths.

A fresh community outbreak in mid-August required a second, six-week lockdown in largest city Auckland, but the country has fared better than many of its peers. U.K. GDP fell 9.6% in the third quarter from a year earlier, while Australia’s fell 3.8%.

The government pledged NZ$62 billion ($44 billion) of fiscal support to help revive domestic demand and protect jobs, while the central bank has slashed interest rates and embarked on quantitative easing and term lending programs to further drive down borrowing costs.

That’s put a rocket under the housing market, with prices soaring to fresh records.

Government Signals Unease With RBNZ’s Requested Housing Tool

Still, the Reserve Bank and some economists have cautioned the economy may contract in the fourth quarter and even face a double-dip recession early next year, citing slower global growth and the possibility that the border will remain closed to most visitors until at least the second half of 2021.

Other Details

The third-quarter expansion was driven by construction and services industries — in particular retailing, accommodation and restaurants, the statistics agency said.

- Manufacturing output rose 17% from the second quarter

- Construction jumped 52%

- Household consumption increased 14.8% led by cars, televisions and domestic air travel

- Investment surged 27% led by residential building

- Exports rose 4.9%, while imports gained 10.6%

- GDP per capita climbed 13.8%

Further Reading

I regularly answer reader questions on adamfayed.com, Quora, YouTube and beyond.

In the article below, which was taken from my online Quora answers, I discuss:

- Can somebody on a middle-class income become rich or wealthy, or is it unrealistic?

- Do annuities offer good value for money or is drawdown superior for retirees?

- Are house prices likely to go down next year across the board, or will there be a shift in terms of house price inflation? More specifically, I investigate whether prices will rise substantially outside of big cities now more people can work from home.

- Is there such a thing as the safest company in the world to invest in? If not, what is the safest strategy in the investing world to reduce your risks of loses?

Click below to learn more about my answers to these questions