What Is The Endowment Effect In Investing

Understanding and overcoming the endowment effect in investing is crucial for global wealth diversification decisions that maximize returns and minimize biases.

If you are looking to invest as an expat or high-net-worth individual, which is what I specialize in, you can email me (advice@adamfayed.com) or WhatsApp (+44-7393-450-837).

Introduction

Learn about the endowment effect and its implication for investing and marketing, as well as what its cause is and how to avoid it.

The endowment bias explains why an offering’s expected value is greater than its market value. Again, the likelihood of it happening in circumstances involving objects with sentimental, symbolic, or financial significance is high.

What is the Endowment Effect

A behavioral psychology concept known as the endowment effect describes people’s propensity to place a higher value on an object they own than they would place on it if they did not.

They frequently overestimate the fair market value of an owned item when valuing it. Additionally known as the “ownership effect,” the endowment effect has other names.

The endowment effect states that the highest price that people will typically pay for something they don’t own is less than the lowest price they would be willing to sell the thing for if they did.

Participants in the traditional experiment used to demonstrate the endowment effect were given mugs and asked if they would trade them for some Swiss candies with a higher retail value. Despite this, 80% of the participants refused to make the trade.

The loss-aversion psychology theory, which holds that people place a higher value on losing something than gaining something, is frequently held to be the root of the endowment effect.

One study, for instance, discovered that employees put in more effort to maintain their eligibility for a bonus that had already been provisionally awarded to them than they did for a higher bonus that they might receive in the future.

Understanding the Endowment Effect

Other psychological explanations for the endowment effect have been put forth in addition to loss aversion.

According to the psychological inertia theory, unless given a strong incentive to do otherwise, people prefer to maintain the status quo in their lives, including keeping possession of the things they already own.

According to connection-based or attachment theories, once a person owns something, it becomes a part of their self-identity and they develop an emotional attachment to it that goes beyond the material value. As a result, selling the item and losing it emotionally presents a threat to the identity the person holds dear.

How Does Endowment Effect Work?

The endowment effect shows that people form different values for an object in their minds before and after they possess or use it. When compared to a non-owned item, people value owned items more favorably.

When someone owns something, their estimation of its usefulness increases. The endowment effect is supported by a number of theories, including loss aversion, status quo bias, and psychological inertia.

Loss Aversion

The idea states that if an event has two possible outcomes, one is gain and the other is comparable loss. Simply put, the level of pain felt after losing something outweighs the level of enjoyment felt after obtaining it. Individuals will naturally seek to avoid losses rather than gain from the situation.

Status Quo Bias

It’s common for people to maintain the status quo. Many factors, including emotional attachment and loss aversion, explain why people prefer to stay put in their current circumstances.

Psychological Law of Inertia

It shows that people tend to keep things as they are unless they are motivated to change them.

Numerous other theories, such as the motivated taste change theory and reference price theory, are also used by researchers to explain the endowment bias. The reference price theory contends that different trading parties have unique reference points that affect their choices.

For instance, a buyer expects the price to reflect the value of the product, while a seller will not like to price a product below market value.

According to the motivated taste change theory, an item’s utility increases in the owner’s eyes after they acquire it, which affects their choices when they decide to buy it again.

Example of the Endowment Effect

Let’s examine a case in point. A relatively inexpensive case of wine was purchased by the individual.

The endowment effect might compel the owner to decline this offer, despite the financial gains that would be realized by accepting it, if an offer were made later to buy that wine for its current market value, which is just a little bit higher than the price that the individual paid for it.

The owner can therefore decide to wait for an offer that meets their expectations or consume the wine themselves rather than accepting payment for it.

Due to actual ownership, the person overestimated the wine’s value. Similar responses, fueled by the endowment effect, can have an impact on businesses as well as collectibles owners who value their possessions more than anything else.

Such behavior is irrational in accordance with the restrictive presumptions of rational choice theory, which forms the basis of contemporary microeconomic and financial theory.

Such allegedly irrational behavior is explained by behavioral economists and behavior finance scholars as the result of a cognitive bias that distorts the person’s thinking.

These theories hold that a rational person would value a case of wine at the exact market price since they could buy an identical case of wine at that price if they were to sell or otherwise part with their current case.

What is the Endowment Effect in Investing?

In the context of investing, the endowment effect has been proven numerous times. Investors have repeatedly shown to be reluctant to sell stocks that are underperforming and less likely to exchange them for ownership of a stock that is similar but performing better.

The endowment effect’s proposed attachment theories would appear to be supported by this kind of behavior.

What is the Implication of the Endowment Effect in Marketing?

Businesses have attempted to incorporate the endowment effect into their sales strategies in a variety of ways because it has significant implications for the marketing of goods.

The free trial is a prime illustration of how to use the endowment effect to boost a product’s sales. Dealerships frequently provide free two- or three-day rental periods for potential customers who want to take a car home and test drive it.

It is clear that the goal is to foster a sense of attachment and ownership that will encourage someone to buy the car.

Customers can try other products for free for 30 days. Once more, it’s a ploy to make the customer feel as though they already possess the product, making them resentful of having to return it at the end of the trial period.

Other businesses have used sales strategies that don’t involve having a product in your hands but still try to instill a sense of ownership in a potential customer.

For instance, Converse uses computer imaging to let customers choose the color or style of a pair of shoes. Consumers have been shown to be more likely to purchase when they personalize their purchase.

Customers can freely handle products as much as they’d like in Apple stores in order to foster a sense of attachment.

When businesses use the second-person form of address to describe their products, such as “Your (product “x”) will make your morning routine easier and more enjoyable,” they are making a more covert attempt to take advantage of the endowment effect.

Causes of the Endowment Effect

There are two primary psychological factors that account for the endowment effect, according to research:

Ownership

A bird in the hand is worth two in the bush, and studies have repeatedly shown that people will value something they already own more than a similar item they do not own, regardless of whether the object was purchased or received as a gift.

Loss Aversion

The prospect of selling these assets or trades at the current market value does not correspond to investors’ perceptions of their value, which is the main reason why investors frequently stick with certain unprofitable assets or trades.

Most often, loss aversion—the idea that we dislike losing things more than we like gaining them—is used to explain how the endowment effect arises.

When faced with a choice, loss aversion causes us to prioritize what we stand to lose rather than what we stand to gain. As a result, we tend to favor maintaining the status quo over making changes that could result in losses.

In one experiment conducted by Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky, two of the pioneers of behavioral economics, subjects were instructed to visualize themselves in either Job A or Job B.

They were informed that they could choose to transfer to either job, A or B. In some ways the new job was better than their old one, but in other ways, it was worse.

No matter which job they initially held, Kahneman and Tversky discovered that the majority of people did not want to switch to the other one.

We frequently underestimate opportunity costs when making decisions, which is another aspect of loss aversion.

Unlike out-of-pocket costs, which are the upfront payments you make in a transaction, opportunity costs are the benefits we forgo when we select one alternative over another.

When we try to overcharge a buyer for something we own, the endowment effect explains that we do so in part because we are more concerned with the out-of-pocket expense (losing that item) than we are with the money we will lose if the buyer rejects our price.

Buyers and Sellers Value Things Differently

Although the endowment effect was initially solely attributed to loss aversion, other researchers have proposed a few other theories that are more convincingly supported by the data.

One of these is from a 2012 paper by Ray Weaver and Shane Frederick, who contend that people attempt to avoid being duped into a bad deal when the endowment effect actually occurs. Reference price theory is the name given to this viewpoint.

This point of view contends that when buyers and sellers approach a transaction, they frequently have various reference prices or notions of what something is worth.

In other words, if you were trying to sell a mug that normally retails for $3, you probably wouldn’t want to settle for anything less than that because then you would feel like you’re losing out.

Similarly, buyers don’t want to pay more than they believe an item is worth, but sellers don’t want to sell for less than that item’s market price. However, $1 might be the highest price a customer is willing to pay if they are only tangentially interested in purchasing a new mug.

The endowment effect, in other words, occurs when there is a discrepancy between a buyer’s willingness to pay and a seller’s willingness to accept a particular price.

The reason for this discrepancy can sometimes be found in the fact that buyers will often use the lowest price that is readily available as a benchmark while sellers will use the highest.

For instance, you might feel like a slacker if you sold a ticket for a basketball game for less than $400 if you saw that others were reselling similar seats for $400.

People who are looking to purchase tickets similar to yours see that others have sold for a price that is closer to the original, so they are unwilling to pay your higher price.

Our Positive Self-Concept is Reflected on Our Possessions

The fact that we enjoy things more when we relate them to ourselves is another potential explanation for the endowment effect.

We are biased to see ourselves in a positive light and frequently believe that we are exceptional in various ways, whether it is justified or not (and it is very frequently not).

This view of ourselves, according to research, even encompasses the things we own. The mere ownership effect is what is meant by this.

University students who took part in a study on the mere ownership effect were informed that they were taking part in a consumer preference study and that their task was to simply rate the attractiveness of a variety of goods, such as chocolate, a key ring, and soap.

A plastic drink insulator—a tube you can wrap around cans to keep them chilled—was one of the items. Some of the participants were told they would receive a drink insulator as a “thank you” gift for taking part in the study, which was designed to find out whether people had stronger feelings about things they owned.

You’re right if you think receiving a plastic tube would be a dull gift; the researchers made this decision after discovering that participants’ opinions of the drink insulator were largely indifferent in a different study.

Despite how uninteresting this item usually is, the researchers discovered that participants who received it as a gift thought it was more appealing than participants who were not given a gift.

This theory has an intriguing implication: If one feels threatened by their self-concept, one is even more motivated to improve one’s mental image of oneself. In fact, one study discovered that recipients of a drink insulator as a gift rated it as more enticing than recipients who had not received negative feedback, even after receiving a poor rating for their performance on a task.

Actual Ownership Differs From Psychological Ownership

Even if something isn’t actually ours, we might still feel a sense of ownership over it.

How much it takes for us to feel ownership over something has been the subject of extensive research, and it turns out that it doesn’t take all that much. This indicates that the endowment effect has a relatively low threshold as well.

In one experiment, researchers handed out chocolate bars to each participant and set them on their desks, but they also told them they weren’t allowed to eat the chocolate. The chocolate bar stared down the participants as they worked on a project for thirty minutes.

The participants were finally informed that the chocolate bar was theirs by the researchers after the project was completed. The option to keep the chocolate or to sell it back at a price they chose was presented to the public before they left.

Participants who resold the chocolate bar did so on average for $1.72. The endowment effect was at work when a different group of participants received the chocolate bar as a reward at the conclusion of the project rather than having it sit on their desks for 30 minutes.

This study demonstrates how psychological ownership can develop quickly. The ability to touch a product prior to purchase is one of the many other methods that people can be made to feel a sense of ownership, according to additional research.

The Impact of the Endowment Effect

People who inherit stock from departed family members display the endowment effect by refusing to sell those shares, even if they don’t match their risk appetite or investment objectives.

This can negatively affect the diversification of a portfolio. To minimize negative effects, it is necessary to assess whether the addition of these shares has a negative impact on the asset allocation as a whole.

Outside of finance, the endowment effect bias is also present. A well-known study that has been successfully replicated begins with a college professor who teaches a class with two sections, one that meets on Mondays and Wednesdays and another that meets on Tuesdays and Thursdays. This study is an example of the endowment effect.

The professor doesn’t make a big deal out of giving the Monday/Wednesday section a brand-new coffee mug with the university’s logo emblazoned on it as a gift. On the other hand, nothing is given to the Tuesday/Thursday section.

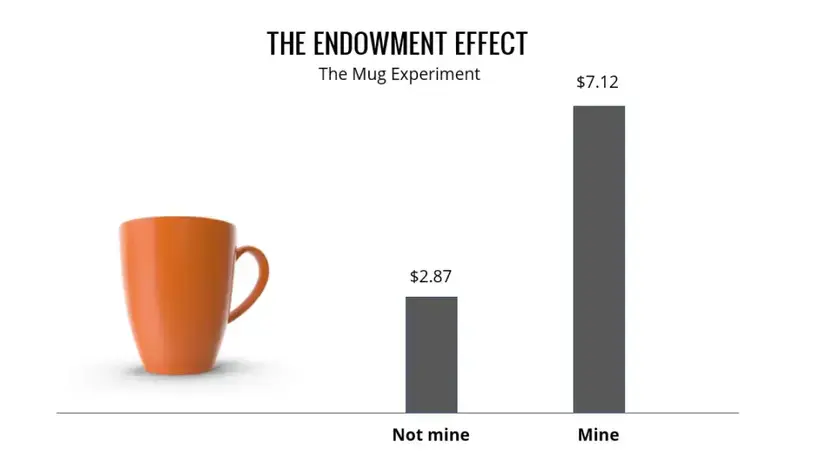

The professor asks each student to assign a value to the mug a week later. On average, the students who received the mug valued it higher than those who did not.

When asked to estimate the lowest possible selling price for the mug, the students who received one consistently and significantly higher estimates than the students who did not receive one.

How to Avoid the Endowment Effect

Avoid Taking Psychological Ownership

It’s common practice for salespeople to encourage customers to picture themselves driving a particular model when they are in the market for a new vehicle, and of course to allow test drives.

Of course, having the opportunity to test drive a car before you purchase it is crucial to get a feel for it, but these strategies are also intended to promote psychological ownership.

It gets harder to part with a product the longer you use it and interact with it because it begins to feel more like yours.

Be wary of sales tactics and salespeople who attempt to create a “bond” between you and their products.

When you do encounter them, try to remember that just because you had a brief interaction with a product, it doesn’t necessarily mean it’s better than your other options or that you should spend a lot more money on it.

Think About Opportunity Costs

You might be tempted to overprice something when trying to sell it, perhaps because it has sentimental value or because you don’t want to lose out on the extra cash you could possibly make by charging so much.

However, bear in mind that pricing your item higher than market value or at the upper end of what people typically sell it for will make it harder to draw in a buyer—especially if they can get the same thing somewhere else, for less money.

Selling something for close to its value is preferable to never selling it at all.

Set Your Prices Based On Market Value

Being closer to market value is one of the easiest ways for a seller to avoid being victim to the endowment effect. Weaver and Frederick demonstrate in their paper that the endowment effect disappears when both parties value the item at its market price.

Try to stay in the middle of the price range if there is one for this item. When buyers and sellers have similar reference prices in mind, there is typically less of a difference between their willingness to pay and their willingness to accept.

Pained by financial indecision? Want to invest with Adam?

Adam is an internationally recognised author on financial matters with over 830million answer views on Quora, a widely sold book on Amazon, and a contributor on Forbes.